Chairman Mao once pluckily said that a journey of a thousand miles (although it was probably 'Li' and not miles) begins with a single step, though I don’t know whether he said this before or after the infamous “Long March” of 1934. Unfortunately, I'm more likely to treat the beginnings of things as if I were Zeno, seeing every segment of that thousand-mile journey as consisting of an infinite number of first steps, preventing me from ever reaching my goal. Lately, I’m inclined to hitch my wagon to Heraclitus (it's a small wagon) and treat the whole project as a process that doesn't necessarily have a beginning, ending or middle -- just a gradual change captured as snapshots that will find themselves posted on this blog. So what's the project?

BABBLE/ON IS A CITY

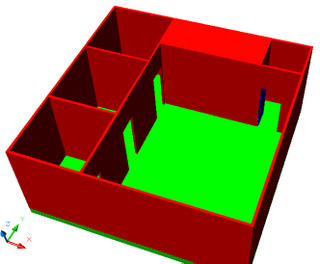

The short answer is that I'm going to design a city. For now, it will be created entirely on a computer using CAD software that allows for 3D modeling of buildings and landscapes. There will be residences, municipal buildings, office towers, power plants, public parks and monuments, museums, transit hubs and just about anything else that you can find in a city. Parts of the city will be boring or purely functional while other parts will be fanciful and weird. I will design some things to be as realistic as possible and others that would be physically impossible to build. Sections of the city will be an obvious homage to a certain style or a near-exact replica of an actual place, but there will be other places that will look like something out of a space opera. The city will be absolutely everything and anything I can dream up.

BABBLE/ON IS A PERSONAL PROJECTThe reason I’m designing such an eclectic city is because I want to teach myself how to draft in 3D, with the aim of pulling off a big career change. I’m not sure if I’ll be going into architecture, urban planning, industrial design or engineering, but I know that I enjoy computer drafting and I like the idea of helping to design things that will be useful to people. I’ll explore my background and motivations in a future post, but suffice it to say that I would enjoy creating things for a living.

I’m hoping that in creating this city, I will learn how to draft in 3D using CAD software, be able to explore and internalize basic design concepts, get a feel for the basics of urban planning and have a regular creative outlet that syncs up with my career goals.

BABBLE/ON IS A WEBLOGAfter I came up with the idea of building a virtual city to teach myself how to draft in 3D, it occurred to me that it would also be a pretty good blog idea. A blog is something like being a published writer and also a little like being a radio dj, both of which I’ve enjoyed doing before, so the idea has a lot of appeal to me. I tried my hand at it with a music-themed blog that never really held my attention. Since that died a lingering death, I’ve been keeping my eyes open for a blog idea that I could really get into, and I think I’ve found it.

On these virtual pages you’ll see the city of Babble/On as it begins – slowly – to develop, and at the same time you’ll hopefully see my drafting skills improve. Perhaps any savvy creative types out there will be able to see an increasing sophistication in my design sensibilities, although I’m far less optimistic about this. There will also be some occasional tech-talk about the computers and software that I’ll be using, with the inevitable glitches and support issues that come up, although I’ll try to keep this to a bare minimum.

I hope that having such a public forum will keep me honest about working regularly on the project and help me to clarify my thinking as I go. I also hope that I’ll get some regular readers that can help to critique my plans, give me hardware/software tips and join me in a general dialogue about the world of design and my project. If I get to a point where people think that I’ve learned things that they want to know, I’ll be happy to share.

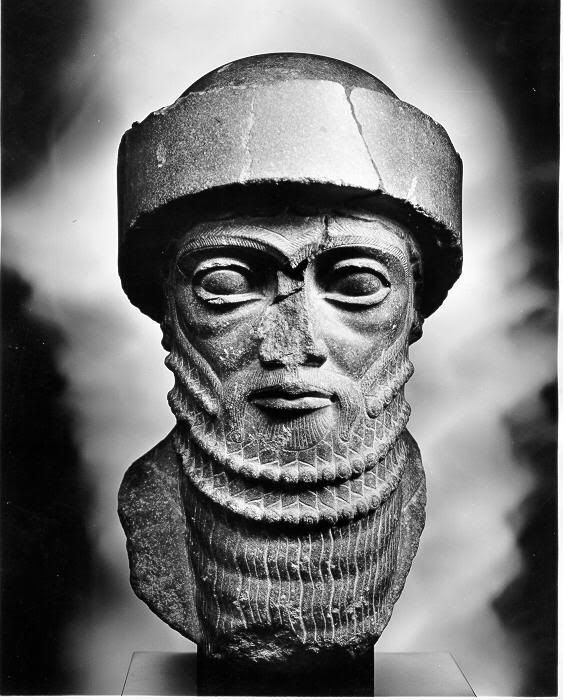

THE RECTIFICATION OF NAMESConfucius was really big about calling things by their proper name, and I must admit to a certain obsession in that regard as well, though not in the way he was talking about. “Babble/On” is of course a pun on the ancient city “Babylon” and my tendency to “babble on” and on about whatever happens to be floating my boat. So caveat emptor: I like puns. I also live in New York, a city which is frequently compared to the famously wicked Babylon because of all the fun depravity and excellent rocking out to be found here.

Also, for the time being I will be keeping this blog anonymous because I work in a design office and may occasionally discuss work situations if they pertain to some aspect of the design and construction world that comes up on the blog. I have taken the nom de blogue “Arazu” because he was a Babylonian god of completed construction. I realize that this might be a bit too Dungeons & Dragonsey for some, but it’s better than calling myself Marduk or Gilgamesh.

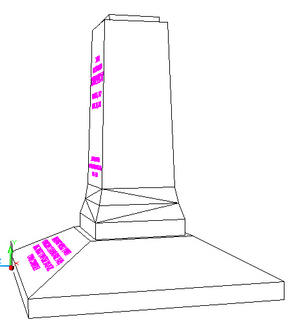

Finally, in the spirit of beginnings, I'll attach a screenshot of the second 3D project I did (about two weeks ago), a simple rendering of a bench that I did for a construction project at work. I had a side elevation to work with on computer, so I just went into the field and took the remaining measurements, whipped it up in CAD and did a quickie fill. Enjoy.

As you can see, it looks a bit more realistic than the

As you can see, it looks a bit more realistic than the